Becoming a park ranger was a childhood dream of mine. In fact, creating and maintaining this blog is probably a way of managaing that missed dream. As a kid, I was was subscribed to Ranger Rick Magazine which has been around since 1967 is still around to this day. So, how does one become a Park/Forest Ranger? Stick around and find out in this exhaustive guide!

Forest rangers protect some of America’s most treasured landscapes while working outdoors every single day. If you’ve dreamed of a career combining adventure, conservation, and public service, becoming a forest ranger might be your path. But the journey requires specific education, training, and dedication that many aspiring rangers underestimate.

I’ll write a comprehensive guide on becoming a forest ranger that’s better than the reference articles and follows all your specifications.

How to Become a Forest Ranger: Your Complete Guide to Starting a Rewarding Career in Conservation

Forest rangers protect some of America’s most treasured landscapes while working outdoors every single day. If you’ve dreamed of a career combining adventure, conservation, and public service, becoming a forest ranger might be your path. But the journey requires specific education, training, and dedication that many aspiring rangers underestimate.

This comprehensive guide cuts through the confusion about forest ranger careers. You’ll learn the exact educational requirements, essential skills, salary expectations, and realistic timelines for entering this competitive field. We’ll distinguish between different ranger roles, explain what daily work actually involves, and reveal insider strategies for landing forest ranger jobs. Whether you’re a high school student planning ahead or a career-changer seeking outdoor work, this article provides the roadmap you need to start your career as a forest ranger.

What Does a Forest Ranger Actually Do?

The duties of a forest ranger extend far beyond what most people imagine. Forest rangers work to protect natural resources, manage public lands, and ensure visitor safety across millions of acres. A typical day might include patrolling trails, monitoring wildlife populations, responding to emergencies, and educating the public about conservation. The job combines outdoor fieldwork with administrative responsibilities, law enforcement duties, and resource management tasks.

Forest rangers and park rangers share some responsibilities but serve different roles. Forest rangers typically work for federal or state forest services, focusing on forest management, timber resources, and wildfire suppression. They spend considerable time in backcountry areas monitoring forest health and managing ecosystems. Park rangers generally work for the National Park Service or state parks, with greater emphasis on visitor interaction and park facilities. However, these distinctions blur significantly in practice, with many positions incorporating elements of both roles.

The range of responsibilities varies by agency and location. Conservation law enforcement represents one major focus for many rangers. Law enforcement rangers have police authority to enforce regulations, investigate crimes, and conduct search and rescue operations. Other forest ranger roles emphasize resource management, requiring expertise in forestry, wildlife management, or ecosystem science. Some positions focus on fire management, while others prioritize environmental education programs. Understanding these specializations helps you target the forest ranger career path that matches your interests and skills.

Forest rangers play a crucial role in conservation efforts nationwide. They monitor wildlife habitats, conduct wildlife surveys, and implement habitat restoration projects. Rangers manage controlled burns to reduce wildfire risk and improve forest health. They work with scientists studying everything from endangered species to climate change impacts. This conservation work makes ranger positions essential for protecting America’s natural heritage while balancing public access with ecosystem preservation.

What Education Requirements Must You Meet?

The educational requirements for forest rangers depend on the specific position and agency. Most forest ranger jobs require at least a bachelor’s degree in a relevant field. Forestry programs provide the most direct path, covering tree identification, forest ecology, silviculture, and resource management. Environmental science, natural resources management, wildlife biology, and environmental conservation also prepare you well for forest ranger roles. Some positions accept degrees in biology, ecology, or related sciences if combined with relevant coursework.

A bachelor’s degree in a relevant field typically takes four years to complete. Your coursework should include forest ecology, wildlife management, botany, soil science, and resource management. Many programs require field courses where you gain hands-on experience with forest inventory techniques, GPS navigation, and data collection methods. Consider programs offering concentrations in fire management, recreation management, or conservation law enforcement if you know your preferred specialization. Internships during your undergraduate years provide invaluable experience that strengthens job applications significantly.

Some entry-level positions accept an associate’s degree combined with substantial field experience. Two-year programs in forestry technology or natural resource management can open doors to seasonal or technician positions. However, advancement to permanent forest ranger positions usually requires a bachelor’s degree. If you start with an associate’s degree, plan to complete your bachelor’s while gaining experience. Many agencies value work experience highly, so the associate’s degree path can work if you’re willing to start at entry levels and continue your education.

An online degree program offers flexibility for career changers or those unable to attend campus full-time. Several accredited universities now offer forestry and natural resource management degrees online. These programs work best if you already have outdoor skills and can arrange local fieldwork opportunities. However, recognize that hands-on experience remains crucial. You’ll need to supplement online coursework with internships, volunteer work, or seasonal positions to develop the practical skills agencies expect. The job market for forest rangers favors candidates who combine strong academics with demonstrated field experience.

Is It Difficult to Become a Forest Ranger?

Yes, becoming a forest ranger requires significant effort and competition is intense. The difficulty stems from limited positions, extensive requirements, and many qualified applicants competing for each opening. Most successful candidates spend years building qualifications through education, internships, seasonal work, and specialized training before landing permanent positions. The process demands patience, persistence, and strategic career planning rather than a simple application after graduation.

The competitive nature varies by agency and location. Federal positions with the US Forest Service or National Park Service attract hundreds of applications for single openings. State parks systems vary widely, with some states offering more opportunities than others. Remote locations throughout the state often have less competition than popular destinations near urban areas. Seasonal positions become available more frequently than permanent roles, making them a common entry point. Many forest rangers spend several years working seasonally before securing permanent forest ranger jobs.

Requirements to become a forest ranger include more than just education. Physical fitness standards ensure rangers can handle demanding field conditions. You must pass background checks and drug screenings. Law enforcement positions require completion of law enforcement training academies lasting several months. Many positions require a valid driver’s license and willingness to relocate to remote areas. Some agencies require U.S. citizenship. Emergency medical training enhances your competitiveness. Search and rescue experience, wildfire qualifications, and specialized certifications all improve your chances.

Building a competitive application takes strategic planning. Start gaining relevant experience during high school and college through volunteer work, internships, and summer jobs. Seasonal positions with government agencies provide the strongest foundation. Develop diverse skills including GIS, wildlife monitoring, public speaking, and law enforcement. Network with rangers and attend career fairs. Be willing to start anywhere and relocate frequently early in your career. Success often requires accepting temporary positions, gaining experience in multiple locations, and persistently applying until you build the resume that secures a permanent role.

How Much Do Forest Rangers Get Paid in the US?

Forest ranger salaries vary considerably based on experience, location, agency, and specific responsibilities. Entry-level positions typically start between $35,000 and $45,000 annually. Mid-career rangers with 5-10 years experience generally earn $50,000 to $70,000. Senior rangers and those in supervisory roles can earn $70,000 to $90,000 or more. Federal positions often pay slightly more than state roles, though benefits packages vary. Geographic location significantly impacts pay, with rangers in high cost-of-living areas receiving higher salaries through locality adjustments.

Law enforcement rangers typically earn higher salaries than rangers focused primarily on resource management. The law enforcement focus comes with additional training, responsibilities, and risks that justify premium compensation. Rangers with specialized skills like fire management, wildlife biology expertise, or search and rescue certifications often command higher pay. Lead ranger positions and park management roles offer increased compensation for supervisory responsibilities. However, many rangers emphasize that salary represents just one component of the career’s total value.

Benefits often make ranger positions more attractive than base salary alone suggests. Federal and state government agencies typically provide excellent health insurance, retirement plans, and job security. Rangers often receive housing allowances or free housing in remote locations. Uniforms and equipment are provided. Time off policies are generally generous, with vacation and sick leave accruing reliably. These benefits significantly enhance total compensation, especially compared to private sector jobs with similar base pay but fewer benefits.

The job prospects for forest rangers remain relatively stable but not rapidly growing. Retirements create regular openings as baby boomer rangers leave the workforce. However, budget constraints at federal and state levels limit position growth. Climate change increases demand for wildfire suppression and forest management expertise, potentially creating opportunities. Conservation officers and wildlife protection roles may expand as environmental concerns grow. Overall, expect steady but modest job market growth with strong competition for available positions continuing indefinitely.

What Is the Highest Paying Job in Forestry?

The highest paying jobs in forestry typically involve senior management, specialized consulting, or private sector positions. Forest managers overseeing large private timber holdings can earn $90,000 to $120,000 or more, especially when managing operations for major landowners. Forest consultants advising clients on timber valuation, forest management plans, or conservation strategies often earn six figures. University professors with forestry expertise, particularly those bringing in research grants, can earn substantial salaries. Corporate forestry directors managing sustainability programs for large companies command high compensation.

Within government forestry careers, advancement to regional director or high-level supervisory positions offers the highest salaries. These roles typically require 15-20 years of experience plus proven leadership abilities. Salaries for these positions range from $90,000 to over $130,000 depending on agency and region. However, these positions are extremely competitive and relatively few exist compared to field ranger positions. Success requires not just forestry expertise but demonstrated management skills, political acumen, and extensive experience.

Specialized forestry roles can offer premium compensation. Urban foresters managing tree programs for major cities earn solid salaries, often $70,000 to $100,000, while enjoying better lifestyle amenities than remote forest positions. Fire management officers and incident commanders earn substantial pay, especially during active fire seasons when overtime and hazard pay apply. Wildlife biologists specializing in endangered species recovery can earn $70,000 to $90,000 or more. Forensic foresters investigating timber theft or environmental crimes earn premium rates as consultants.

Private sector forestry generally pays more than government positions for equivalent experience levels. Timber companies, environmental consulting firms, and conservation organizations offer competitive salaries to attract top talent. However, these positions often involve more travel, less job security, and fewer benefits than government roles. A forester working for a timber company might earn 20-30% more in base salary than a government forest ranger but receive less generous benefits and retirement plans. Career choices depend on weighing immediate compensation against long-term security and lifestyle preferences.

Is Forest Ranger a Good Career?

A career as a forest ranger offers exceptional rewards for people who value purpose over pure financial gain. Rangers consistently report high job satisfaction due to meaningful work protecting natural resources and serving the public. Working outdoors in spectacular landscapes provides daily experiences that office workers envy. The combination of variety (no two days are identical), physical activity, and tangible conservation impact makes ranger work deeply fulfilling for people aligned with these values.

The lifestyle suits certain personalities better than others. Rangers must accept remote postings, irregular schedules, and work during holidays when parks see heaviest visitation. Evening and weekend work is standard. Many positions require living in government housing far from urban amenities. Family life can be challenging when stationed in isolated areas with limited schools and services. However, for people who love solitude, outdoor recreation, and small communities, ranger life offers unmatched quality. You’re literally paid to live in places others vacation.

Job security and benefits represent major advantages. Government employment provides stable income even during economic downturns. The retirement systems for federal and state employees offer defined benefit pensions increasingly rare in private employment. Health insurance coverage is comprehensive. Once you secure a permanent position, you have strong job protection. This security allows rangers to focus on conservation work without constant employment anxiety, though reaching permanent status requires perseverance through temporary positions first.

Career advancement opportunities exist but require strategic planning. Many forest rangers remain field rangers their entire careers, which suits those who love hands-on conservation work. Others progress to supervisory roles, managing teams of rangers and overseeing larger areas. Some transition into specialized positions like wildlife biologist, fire management officer, or environmental educator. Transferring between agencies or moving into related fields like environmental consulting or nonprofit conservation work is common. The experience and skills developed as a ranger create diverse options throughout your career.

What Steps Must You Take to Launch Your Career?

Start building qualifications while still in high school if possible. Take biology, chemistry, ecology, and environmental science courses. Participate in outdoor education programs, scouting, or youth conservation corps. Volunteer at local parks or nature centers. Develop physical fitness through hiking, backpacking, and outdoor skills. These early experiences demonstrate genuine interest while building relevant competencies before you even apply to college programs.

Choose your degree program carefully based on your career goals. Research schools offering strong forestry programs with good job placement rates. Look for programs providing field courses, internship coordination, and relationships with hiring agencies. A degree in forestry from a well-regarded program significantly improves job prospects. Consider location as well since you’ll build regional connections and experience local ecosystems. Many rangers end up working in the same region where they attended school, making program location strategically important.

Gain hands-on experience through every available opportunity. Apply for Student Conservation Association positions offering paid internships on public lands. Work seasonal jobs with the Forest Service, National Park Service, or state agencies. Volunteer for trail maintenance projects, wildlife surveys, or visitor education programs. Each experience builds your resume while helping you understand what ranger work actually involves. Many permanent rangers started with internships or seasonal positions and impressed supervisors enough to earn recommendations or preference when positions opened.

Obtain necessary certifications and specialized training to stand out from other applicants. Complete wilderness first aid or EMT training. Earn chainsaw certifications. Take GIS courses. Complete wildfire training (Red Card qualification). Get boating safety certifications if aquatic resources interest you. Law enforcement training obviously helps for enforcement positions but also demonstrates commitment. These specialized qualifications move your application to the top of piles when hiring managers review candidates.

How Do Forest Rangers and Park Rangers Differ?

Forest rangers typically work for the U.S. Forest Service or state forestry agencies managing forested lands. Their primary mission focuses on sustainable forest resource management, including timber harvesting, watershed protection, and ecosystem health. Forest rangers work in national forests covering 193 million acres across the country. They deal extensively with forest fires, managing both suppression and prescribed burns. Timber sale administration, forest inventory, and reforestation projects consume significant time. While public interaction occurs, forest rangers often spend more time on resource management than visitor services.

Park rangers generally work for the National Park Service or state parks systems emphasizing preservation and visitor experience. The National Park Service may assign rangers to historical sites, natural areas, or cultural parks. Visitor interaction and park interpretation are central to most park ranger roles. Park rangers lead educational programs, staff visitor centers, patrol campgrounds, and answer questions about park resources and regulations. While they also protect resources, the balance typically leans more toward public engagement than forest rangers experience.

Law enforcement authority varies between positions but many rangers of both types have police powers. Conservation law enforcement officers in either system enforce regulations, investigate violations, and maintain public safety. Some agencies distinguish between interpretation rangers who focus on education and law enforcement rangers who handle citations and arrests. However, in practice, many rangers perform both functions, especially in smaller parks or forests where staff must be generalists. The specific job duties depend more on individual position descriptions than the forest ranger versus park ranger title.

Career paths can lead to either role or both over time. Some agencies use similar hiring systems, making it possible to move between forest and park positions. Rangers might start with seasonal work in state parks, move to a permanent forest ranger position, then later transfer to the National Park Service. The core competencies overlap substantially even though daily emphasis differs. Understanding these nuances helps you target applications toward positions matching your interests whether they’re titled forest ranger, park ranger, conservation officer, or something else entirely.

What Agencies Hire Forest Rangers?

The U.S. Forest Service represents the largest federal employer of forest rangers. As part of the Department of Agriculture, the Forest Service manages 193 million acres across 154 national forests and 20 national grasslands. Forest Service careers include wilderness rangers, recreation managers, timber sale administrators, fire managers, and wildlife biologists. The agency hires both seasonal and permanent staff, with career ladders allowing advancement from entry positions to district rangers managing large areas. Competition is intense but opportunities exist for qualified candidates willing to start anywhere.

The National Park Service offers positions across 423 sites including national parks, monuments, historic sites, and recreation areas. While titled park rangers rather than forest rangers, these positions offer similar work for conservation-minded candidates. The National Park Service may emphasize interpretation and visitor services more than the Forest Service, but law enforcement, resource management, and back-country patrols remain central duties. The agency is part of the Department of Interior and follows similar federal hiring processes as the Forest Service.

State parks systems in all 50 states employ rangers in various roles. Each state operates independently with its own hiring processes, qualification requirements, and organizational structures. Some states offer extensive park systems with hundreds of positions, while others have smaller operations. State positions often provide better work-life balance than federal roles and keep you in a specific region rather than requiring nationwide mobility. However, salaries and benefits vary considerably by state. Research your target state’s system thoroughly since policies differ dramatically.

Additional government agencies offer related positions worth considering. State departments of natural resources hire conservation officers and wildlife rangers. The Bureau of Land Management manages vast public lands requiring ranger staff. State forestry departments employ forest protection specialists. County and municipal parks need rangers for local systems. Each agency has distinct missions, cultures, and hiring processes. Broaden your job search beyond just Forest Service and Park Service to maximize opportunities for getting hired and building experience that later opens doors to your ideal position.

What Challenges Do Rangers Face Daily?

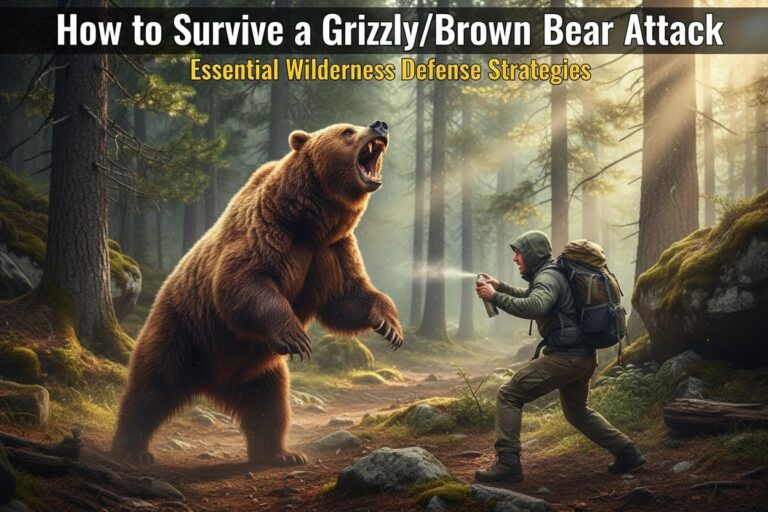

Physical demands require excellent fitness and tolerance for harsh conditions. Rangers hike long distances carrying heavy packs in difficult terrain. You’ll work in extreme heat, cold, rain, and snow. Some positions require helicopter operations, technical rope work, or swift water rescue capabilities. Injuries from slips, falls, or encounters with wildlife pose real risks. The work is physically exhausting, especially during emergency responses or fire season. If you prefer climate-controlled environments and predictable physical demands, ranger work will challenge you significantly.

Dealing with difficult visitors tests patience and communication skills. Rangers regularly encounter people violating regulations, behaving dangerously, or simply being rude and entitled. You’ll issue citations to angry individuals, evacuate reluctant campers during emergencies, and enforce unpopular rules. Some visitors question your authority or expertise. Balancing enforcement with education requires skill, especially when you’d prefer to help rather than cite someone. Law enforcement aspects of the job create stress that not everyone handles well long-term.

Budget limitations frustrate rangers who see critical work going undone. Staffing shortages mean longer hours and postponed projects. Equipment may be outdated or insufficient. Training opportunities might be limited. Deferred maintenance affects park facilities and visitor experience. Rangers who entered the field idealistic about conservation sometimes feel demoralized by resource constraints preventing them from accomplishing their missions fully. Success requires accepting these limitations and finding fulfillment in the work you can accomplish despite system limitations.

Career uncertainty early on creates planning challenges for aspiring rangers. Seasonal positions dominate entry-level opportunities, meaning gaps between jobs, lack of benefits, and income instability. You’ll likely need to relocate frequently chasing opportunities. Building permanent status takes years. This uncertainty makes starting families, buying homes, or establishing roots difficult. Some people burn out before reaching permanent positions. Understanding this reality upfront helps you plan financially and emotionally for the years it takes to establish yourself in forest ranger careers.

Your Path Forward: Essential Points to Remember

Starting your journey toward becoming a forest ranger requires understanding these critical realities:

- Education requirements start with a bachelor’s degree in forestry or related field. Most positions require four-year degrees, though some entry-level roles accept associate’s degrees with experience. Choose programs with strong field components and internship opportunities.

- Competition for permanent positions is intense and requires patience. Plan for several years working seasonal jobs while building qualifications. Be willing to relocate anywhere and accept temporary positions initially.

- Forest rangers earn $35,000 to $90,000 depending on experience and role. Entry-level positions start lower but federal benefits and job security enhance total compensation. Law enforcement specializations typically pay more.

- Physical fitness and outdoor skills are non-negotiable requirements. You must handle demanding field conditions, remote locations, and sometimes dangerous situations. Maintain excellent fitness throughout your career.

- Hands-on experience matters as much as education. Internships, seasonal work, and volunteer positions provide the resume strength that lands permanent jobs. Start gaining experience immediately.

- Forest rangers differ from park rangers in mission emphasis. Forest rangers focus more on resource management and timber, while park rangers emphasize visitor services. However, roles overlap significantly in practice.

- Multiple agencies hire rangers with varying qualifications. Don’t limit applications to just Forest Service or Park Service. State agencies, BLM, and other organizations offer excellent opportunities.

- The career offers high satisfaction but modest pay and difficult lifestyle. Rangers consistently report loving their work despite challenges. The job suits people valuing purpose over money.

- Specialized certifications improve hiring prospects dramatically. Wildfire qualifications, EMT training, law enforcement academy, GIS skills, and rescue certifications all strengthen applications significantly.

- Career advancement requires strategic planning. Decide whether you want field work long-term or aim for supervision and management. Build skills supporting your chosen direction.

- Job security and benefits compensate for moderate salaries. Government employment provides stability, pensions, health insurance, and other benefits increasingly rare in private sector jobs.

- Becoming a forest ranger requires genuine passion for conservation and public service. The work is too demanding for people motivated purely by outdoor recreation preferences. Success requires commitment to resource protection and public education missions.

Becoming a forest ranger means committing to a career of service, sacrifice, and deep satisfaction. The path requires years of preparation, strategic experience building, and persistence through competitive hiring processes. You’ll face physical challenges, budget frustrations, and lifestyle limitations. But for people who love wild places and want careers protecting them, few paths offer more fulfillment. Forest rangers work in spectacular landscapes, contribute to conservation efforts, serve the public, and build careers with purpose. If you’re willing to meet the educational requirements, gain necessary experience, and persist through the competitive hiring process, ranger means a lifetime of meaningful work outdoors protecting America’s natural heritage for future generations. Start building your qualifications today, and you can join the ranks of forest rangers who consider themselves among the luckiest workers in America.